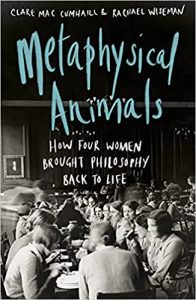

How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life

How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life

by Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman

Published by Chatto & Windus 3 February 2022

416pp, hardback, £25.00

Reviewed by Alison Burns

A quartet of clever twentieth-century British women who brought the narrowing academic discipline of philosophy back to everyday life might not seem the most riveting subject for the general reader. And indeed, there are times when (even to one who studied the same subjects in the same place) this account feels too blithely abstruse. However, the four women in the spotlight are such strong characters, so disarmingly real, and so searching that their chosen subject comes to seem the only one worth arguing about.

Linked by friendship as well as intellectual ability, sharing flats and sometimes lovers (although destined for sharply contrasting private lives), and driven to ask the same central questions over and over, these women were an example of what can be achieved when good brains join forces and refuse to be shouted down.

Iris Murdoch, Mary Midgley, Philippa Foot and Elizabeth Anscombe were philosophy students at Oxford during the Second World War, when most male undergraduates, and many tutors, were conscripted, leaving teaching in the hands of refugee scholars, women and conscientious objectors. They began their philosophical studies shortly after Hitler’s troops entered Austria and fought to rescue metaphysics (e.g. what is a good and what is evil?) from nit-picking logic and hair-splitting linguistic analysis. In due course, young Anscombe publicly challenged the university’s decision to award an honorary degree to US President Harry S. Truman, whose name was by then synonymous with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Notoriously trouser-wearing and chain-smoking, Anscombe went on to become the right-hand woman to philosophy heavyweight Ludwig Wittgenstein, to whose Cambridge Chair she succeeded, while also producing seven children.

Future novelist Iris Murdoch and future environmental/animal ethicist Mary Midgely worked in Whitehall after the war, before returning to academe; Philippa Foot, future leading moral philosopher, helped to set up Oxfam. Against considerable resistance from powerful academic men who found their preoccupations and values too trivial and domestic, too ‘feminine’, these four women threw their energies into demanding ferocious attention to what they saw as the real questions of human life.

The authors, Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman, were lucky enough to get to know the last survivor of the quartet, Mary Midgley, in her nineties and to hear her first-hand accounts of what she called ‘The Golden Age of Female Philosophy’. A measure of the significance of the group – who may have flourished only because of their unique circumstances – is that two biographies have appeared at the same time. The other, published by Oxford University Press, is by American philosopher Benjamin Lipscomb. This one, by two young British female philosophers, is full of passion, colour and insight, as befits their subjects.