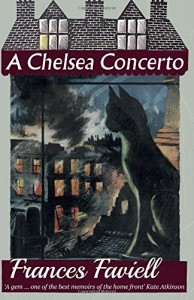

Published by Dean Street Press/Furrowed Middlebrow 3 October 2016

Published by Dean Street Press/Furrowed Middlebrow 3 October 2016

252pp, paperback, £10.99

Reviewed by Elizabeth Hilliard Selka

We think we know all about war – we see enough of it on television, after all. On the one hand it’s horrific, truly disturbing and distressing, and on the other hand it is oh so mundane. Watching the pictures of yet more bombing and human suffering we feel so helpless that we might simply turn off the sound or change channel, or turn away and focus on our own troubles, about which we feel we might be able actively to do something constructive. Or we might count our blessings and be thankful that here in Western Europe we live in conditions of peace and security. In this lifetime wars have often been somewhere else, mostly in hot countries or involving a Muslim population, or both. And even if we knew someone in the military in Afghanistan or Iraq and worried about their safety, they still probably had statistically less chance of being killed or injured than drivers on the roads of Lincolnshire. Continental Europe, over which the Second World War raged, is closer to home but that conflict is now history, ever fewer of those who took part in it still living to bear witness.

A Chelsea Concerto, a memoir by Frances Faviell was first published in 1959. The author was a trained artist, a linguist and much-travelled, a war-time VAD (the same Voluntary Aid Detachment nursing outfit of which Vera Brittain was famously a member in the previous war) and London fire-watcher. The Chelsea of those days has long since been swallowed up to become part of the moneyed entity that is modern Kensington-and-Chelsea, but at that time it was still a village-like community with a strong sense of identity, clearly bounded to the east just beyond Sloane Street by Belgravia, to the north by the Fulham Road, to the west by Lots Road and to the south by the River Thames. Faviell employed a housekeeper at her rented home in Cheyne Walk, adjacent to the Royal Hospital where the red-coated Chelsea Pensioners still live. Not only were rents then such that a community of artists, writers and ordinary working people lived in the area, but the street scene was also quite different– punctuated by corner shops and greengrocers, bakers and butchers plying trade in side streets. It is an appealing picture, another world, into which Faviell drops us immediately into a full-scale civil defence exercise in June 1939, just before the outbreak of war.

In purely historical terms this is interesting – personally I had no idea about local organization of services set up in anticipation of London being bombed, the FAPs (First Aid Posts), CRC or ‘Control’ (Control Report Centre) in the town hall, the Heavy Lifting teams, details of all of which are enlightening and fascinating. The Commissioner of Police Mr Harold Scott ordered that all London traffic be stopped for fifteen minutes for this civil defence exercise; imagine that happening today! Today we are familiar with the importance of fire practices in our places of work, and terrorist attack exercises by the emergency services, but Faviell and her friends felt ‘ridiculous’ lying around pretending to be casualties on the pavements of Chelsea. The phoney war of the year that followed did nothing to dent their confidence – their overriding emotion was boredom, and war was still ‘over there’ in spite of the occasional plane droning overhead. During this spell Faviell has time to focus on local characters – friends and neighbours, shopkeepers, and the refugees billetted in Chelsea with their tragi-comic concerns. Among them is Ruth, a German woman descending into heartbreaking manic dementia, and elsewhere a group of French and Belgians who squabble energetically about the standard of food and cooking facilities supplied to them. Faviell’s fluency in Dutch and Flemish made her the ideal convenor of this latter population, and her warmly intelligent observation brings all Chelsea to life for us on the page.

Thus we are led gently in to the start of the Blitz in 1940… Night after night after night London is bombed, until as we now know 32,000 Londoners were dead and 87,000 seriously injured. With hindsight we also know that the nightly onslaught ended after 57 days, but at the time the inhabitants of London knew no such thing – for all they knew they were never-ending. The raids begin, Frances is busy, and gradually, incrementally, the tension of life in London winds tighter and tighter. No one knew from day to day if they would live or die – yet everyone who did live another day immediately got back to ‘normal’, focussing on the here-and-now, shopping and cooking, relishing fine weather, laughing and loving when possible. Almost in passing Frances mentions that she gets married (because of a raid not one of the guests turned up and neither did the witnesses – passers-by had to be recruited from the street) and, later, she becomes pregnant.

The focus of her narrative is always Chelsea and life lived there in the midst of death and destruction. Death is ever-present; her most horrific duty is to collect scattered body parts from the street after an air raid. Her description of the task and her thoughts and feelings as she tackles it is clear-eyed and unforgettable:

‘After the first violent revulsion I set my mind on it as a detached systematic task. It became a grim and ghastly satisfaction when a body was fairly constructed – but if one was too lavish in making one body almost whole then another one would have sad gaps. There were always odd members which did not seem to fit and there were too many legs. Unless we kept a very firm grip on ourselves nausea was inevitable. The only way for me to stand it was to imagine I was back in the anatomy class again – but there the legs and arms on which we studied muscles had been carefully preserved in spirit and were difficult to associate with the human body at all. I think that this task dispelled for me the idea that human life is valuable – it could be blown to pieces by blast – just as dust was blown by wind… It seemed monstrous that these human beings had been reduced to this revolting indignity by other so-called Christians, and that we were doing the same in Germany and other countries.’

Later in the book she has this job again after Sloane Square tube station suffers a direct hit resulting in ‘a holocaust of human flesh’, so much of it that it had to be stretchered into a nearby house ‘to be pieced together later’. Of one woman who had been known to be in the station, all that was found was ‘one small female piece’. What ‘small female piece’, one wonders with dismay. The smells were often terrible, perhaps ‘the worst thing about it’, and having a cigarette provided the only respite from the stink.

Frances Faviell’s eye-witness narrative of life in the London blitz climaxes with an event effecting her directly which can’t be described without spoiling the drama. Suffice it to say that it is outstandingly traumatic (yet, for those times, appallingly routine), that she survives to tell the tale, and that this entire slim volume is an electrifying read, an education, an emotional roller-coaster, and not to be missed.