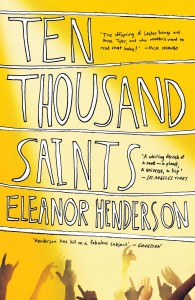

Published by Quercus 28 February 2013

Published by Quercus 28 February 2013

400pp, paperback, £7.99

Reviewed by Lesley Bown

Adolescence can seem like an unlit tunnel, whether you’re the young person going through it or an anxious adult waiting to see who comes out the other end. In her debut novel, American academic Eleanor Henderson charts the perilous journey of a group of teenagers through this tunnel, some of whom may not emerge at the other end.

The setting is very specific –Vermont and New York in 1987 – and the teen subculture of ‘straight edge’ (i.e. no sex, no drugs, no booze) punk. It’ll be hard therefore for most British readers to assess the accuracy or otherwise of the depiction, but this is fiction, not documentary and it’s the story that matters.

The central character is 16-year old Jude Keffy-Horn who is already deep into his personal adolescent wilderness in the opening chapter. Failing at school, sexually frustrated, exploring drugs, he looks like a classic case of a small-town no-hoper. The most important person in his life is his best friend Teddy, but by the end of Chapter Two Teddy is dead, OD’d. From there on the novel charts Jude’s journey from committed stoner through clean-living straight edge band member to – well, let’s not spoil the ending. Running in parallel is the story of Eliza’s pregnancy – the child fathered by Teddy on the night he died.

These first two chapters are a textbook example of how to write an opening, with the balance between giving information and sustaining interest expertly maintained. After that the plot flattens out and works steadily towards an ending that has very few surprises.

At various points we lose sight of the characters where the tunnel grows particularly dark – Jude’s conversion to clean-living for instance happens off-stage. Eventually Jude, Eliza and most of the other teenage characters completely disappear from sight in the summer, when they go on tour with their band. This is described in just a few pages that could be summarised as ‘same old same old’ and yet they return changed, ready to emerge from adolescence.

Henderson writes about the emotionally overwhelming experiences of this problematical phase of life in a cool, detached, non-judgmental voice that contributes to the reader’s sense of dislocation. She describes the various types of dysfunctional parenting that her characters have endured but she doesn’t appear to blame the parents, although it is noticeable that there is not a single grandparent around to create a sense of comparison. The previous generation isn’t relevant to her story and so there is no sense of judgment on the parenting skills of the hippy generation compared with the World War II generation.

She exactly captures the way that teenagers are incomprehensible, not just to adults, but to themselves. Jude doesn’t know why he does what he does, Eliza doesn’t know what to do about the baby, nothing makes sense to anyone. Stuff happens, you struggle through it, and suddenly you’re out of the tunnel. Anyone who remembers their own journey is likely to find much to enjoy in this novel.