Letters from a Conscientious Objector, edited by Peter Jones

Letters from a Conscientious Objector, edited by Peter Jones

Published by Seren 26 October 2018

420pp, hardback, £19.99

Review by Lesley Glaister

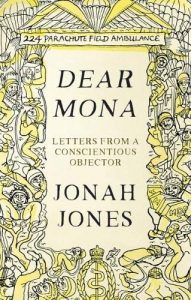

The cover of this attractive volume shows an illustration by Len Jones – Jonah Jones’ original name. The illustration is an amusing cartoon montage of the activities of the 224 Field Ambulance Parachutists and gives a flavour of the mischievous, quirky and non-conformist side of Jones’ personality. The letters within were written between, roughly, 1940 and 1946, and are addressed by Len to Mona Lovell, detailing his occupations during his time as a conscientious objector, and later as a non-combatant serviceman: forester, medic, parachutist, writer, magazine editor, illustrator, librarian and teacher. During these years he was posted to several locations in Britain including Exmoor, Yorkshire and Scotland and subsequently overseas, ending his war in Palestine.

Fifteen years Len’s senior, Mona was a close friend and mentor, whom he met when he became an assistant at her library. The dynamic between them started out romantic – there was even talk of marriage – but Len found himself unable to commit and Mona’s unrequited passion was frustrated by his long equivocation and eventual decision that his feelings could only ever be platonic. Mona was an extraordinarily generous soul; many of the letters mention the thoughtful and helpful gifts she sent him: warm clothes, tobacco, newspapers, food and anything else she thought he might need or want. She was also a selfless mentor, keeping him abreast of her reading and supplied with books, and above all she was a faithful and prolific correspondent. Sadly none of her letters survive, but we get something of the flavour of her voice when Len quotes her back to herself, particularly at moments of exasperation.

Len emerges as a complex personality. He’s funny, sociable – and yet desperate for space and quiet – kind and sensitive, yet horribly judgemental. As often as he is exasperated with Mona’s demands and expectations he castigates himself for his own ambivalence, not just towards her but towards almost all his friends. As we read the fluctuations of his attitudes, emotions and his own self-dramatizing commentary on himself (he seems to identify quite strongly with D.H. Lawrence), the letters sometimes become tedious in their level of introspection. After all, a painstaking self-examination of personality of someone we don’t know is never going to be all that riveting. Even loyal Mona begs him to: ‘Stop that awful soul-searching.’ He quotes this line back to her – and I imagine many readers, like me, will find themselves heartily agreeing with her, particularly since, over the approximate five-year period of the correspondence, the same cycle of elation, excitement, despair and self-castigation recurs many times.

However, outweighing this emotional material there is a treasure trove of concrete information, a particular, nuanced and very human account of the war from the viewpoint of a C.O. Len’s a man who enjoyed food and physical comfort and the physical detail of what it was actually like to live through this time, is fascinating. Towards the end of his service, when he is stationed in Palestine, the letters provide an intriguing insight into the early days of the State of Israel and the fluctuating feelings, both personal and general, towards Jews and Arabs.

As well as the historical interest, the greatest fascination for me in this volume, is the way that we can trace the growth of Len not only from a rather callow boy into a complex and beguiling man, but also into an artist. Having become friends with the poet James Kirkup (whose homosexuality at first repels and later attracts him), he makes attempts at poetry. Len is frustrated by the results of his poetry writing as well as his attempts at fiction, as he finds himself unable to live up to his own vision – something any artist will recognize. He turns to drawing, painting and lino-cutting (materials faithfully supplied by Mona), often excited by his achievement – some of his sketches are included along with the letters – and sometimes in despair, railing against his lack of talent, threatening to give up for ever. Towards the end of the correspondence, he describes a small nude that he carves from a four inch piece of wood and for the first time pronounces himself satisfied, almost in awe of the perfection of this tiny piece of work, a moment of real significance in his development: perhaps the moment when he truly becomes an artist.

In his immaculately written introduction, Peter Jones, son of Jonah, addresses the question of whether he had any right to publish these personal letters in one of which Len has written: ‘I feel letters are between friends only and I want the lovely personal sacredness of those letters to remain unspoiled by others’ reading …’ Peter admits that this presented him with a dilemma, but explains that he decided to publish because ‘… the quality of the letters just seems too good, and their content too important, to leave them languishing in some archive. The story of Len and Mona should be read; let it be a tribute to two extraordinary people.’

I agree with him entirely here and feel privileged to have had access to this collection, which provides both a fascinating and revealing piece of history and a moving human story.