Published by Avon

Quieter Than Killing by Sarah Hilary

Published by Headline

The Legacy by Yrsa Sigurdardottir

Published by Hodder & Stoughton

Sometimes I Lie by Alice Feeney

Published by HQ

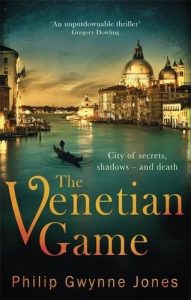

The Venetian Game by Philip Gwynne Jones

Published by Constable

Reading yet another novel about a woman teetering on the edge of mental illness as she tries to live with a manipulative and possibly wicked husband, I have realized that this is the natural sequel to classic romantic fiction. If you buy into the whole romantic lie – When I make a  strong, rich, powerful, clever, handsome man love me, he will save me, pay my bills for ever, and give me a perfect life without my having to make any effort ever again – you are bound to be disillusioned and start to think that you must be mad or else the disappointing non-hero has to be a cruel tyrant to make you so unhappy.

strong, rich, powerful, clever, handsome man love me, he will save me, pay my bills for ever, and give me a perfect life without my having to make any effort ever again – you are bound to be disillusioned and start to think that you must be mad or else the disappointing non-hero has to be a cruel tyrant to make you so unhappy.

The latest example of this particular sub-genre is The Escape by C. L. Taylor. Jo Blackmore, wife of Max, mother of Elise, is  agoraphobic and terminally anxious. Surprisingly, she has a job as a university student support officer, but in her uncontrollable distress she phones her husband so often at work that he’s stopped taking her calls – and so she rings his boss instead. Presented with great sympathy by the author, Jo nevertheless seems wholly incompetent at the start of the novel but gradually takes control of her life and daughter, discovering the shameful secrets of her family’s past as well as some uncomfortable truths about Max. This is a well paced, well structured example of this depressingly popular type of crime novel.

agoraphobic and terminally anxious. Surprisingly, she has a job as a university student support officer, but in her uncontrollable distress she phones her husband so often at work that he’s stopped taking her calls – and so she rings his boss instead. Presented with great sympathy by the author, Jo nevertheless seems wholly incompetent at the start of the novel but gradually takes control of her life and daughter, discovering the shameful secrets of her family’s past as well as some uncomfortable truths about Max. This is a well paced, well structured example of this depressingly popular type of crime novel.

Sarah Hilary and Yrsa Sigurdardottir both write much more interesting and grown-up fiction. Hilary’s Quieter than Killing features DI Marnie Rome, who has one of the toughest family histories in the genre. Her parents fostered a troubled boy, who went on to kill them both in the home where he and Marnie grew up in London. Now in prison, he is at the heart of this revenge drama. Marnie and her sergeant, Noah Jake, have to investigate a series of attacks, which lead them back into her past and present them both with disturbing facts and questions about the damage wreaked on some children and the way that damage can so distort them that they can never live without harming other people. Well written, well researched and full of issues that set you thinking, Quieter than Killing is as impressive as it is gripping.

Yrsa Siggurdardottir explores similar territory in The Legacy. Set in Iceland, it deals with a series of unusually horrible killings, in which electrical equipment is thrust into mouths or ears and switched on. The investigation is divided into three separate strands: Huldar, a relatively junior detective, deals with the official police enquiry; Freyja, an expert in damaged children,  leads the questioning and protection of a very young witness to one of the murders; and Karl, a lonely geek, tries to interpret some bizarre radio transmissions he’s picked up in his basement lair. All the characters are convincing, and Siggurdardottir weaves their pasts and private lives into a wholly satisfying net that draws the reader deep into the mystery.

leads the questioning and protection of a very young witness to one of the murders; and Karl, a lonely geek, tries to interpret some bizarre radio transmissions he’s picked up in his basement lair. All the characters are convincing, and Siggurdardottir weaves their pasts and private lives into a wholly satisfying net that draws the reader deep into the mystery.

Sometimes I Lie, Alice Feeney’s first thriller, is a good example of the coma novel. Her victim is Amber Reynolds, lying unconscious in hospital after a car crash, able to hear and feel everything that goes on around her and yet incapable of making any kind of response. Here, too, we have a possibly cruel husband and an unhappy wife with mental-health issues, but there is more to the plot than the usual straightforward escape-and-be-vindicated theme. The still figure in the bed is the first-person narrator, moving between the distant past, the last few weeks and days, and the present, revealing more and more lies, manipulation, and emotional damage. The pace is fast, in spite of the stillness of the figure in the bed, and the  novel works well.

novel works well.

For any reader who wants refreshment from the miseries of damaged children and brutal psychological distress, Philip Gwynne Jones’s The Venetian Game will be ideal. Featuring the British Honorary Consul in Venice, Nathan Sutherland, it explores that most sinister and beautiful city through the activities of a pair of rich, art-collecting brothers and the delightful Dottoressa Federica Ravagnan, an expert in restoration. This is a civilized, knowledgeable, charming antidote to the darker reaches of the genre, full of entertaining descriptions of the city. ‘I made my way to the Campo San Nicolo dei Mendicoli where the most undignified lion in Venice stood atop a plinth… Shorn of mane, wings and self-esteem, he seemed embarrassed to be up there, like a man who suddenly realizes he’s arrived at work without his trousers.’ Lovely. Makes you want to book a flight to Venice straight away.