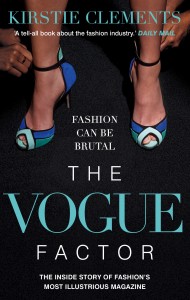

Published by Faber 4 July 2014 UK, Chronicle Books US

Published by Faber 4 July 2014 UK, Chronicle Books US

240pp, paperback, £8.99

Reviewed by Jessica Mann

For a little over a quarter of the century, Kirstie Clements worked for Australian Vogue. Aged 23, she answered an advertisement for a receptionist at the magazine and having talked her way into that job made herself so useful doing other people’s tasks such as tidying the fashion stockroom, reorganizing the drawers containing stockings and socks, packing suitcases and typing, that she was promoted. First an assistant, she worked her way up the hierarchy, eventually, in 1999, becoming editor of Vogue Australia.

Like every other national Vogue, this is a quite independent magazine, commissioning its own material and connected only by ownership to other Vogues. The pecking order is clear, and is dependent on circulation: the American magazine is clearly the most important, while the Australian version, with far fewer readers comes near the bottom of that heap. Never mind: no such considerations held Kirstie Clements back.

Clearly a hero worshipper by nature, she writes with almost childlike reverence about the excitement of photography sessions with, for example, the Crown Princess of Denmark, formerly the Australian Mary Donaldson, or Karl Lagerfeld or Giorgio Armani. Famous names appear on nearly every page, Hollywood celebrities who in Kirstie’s experience are mostly greedy and grasping, and Australian celebrities, ‘who were always a pleasure to deal with, understood our budget constraints, and were fully prepared to take the fashion journey with Vogue.’ Clements never grew out of a naive enthusiasm for ‘all the wondrous events I was invited to be a part of’ – and some of them sound as sybaritic as a Roman emperor’s orgy – but she can be quite acid about some people: social climbers, poseurs and those on a quest for personal glory, but also some of her colleagues, in particular the icy Anna Wintour. ‘There appears to exist some kind of psychological condition that causes seemingly sane and successful adults to prostrate themselves in her presence.’

It’s interesting for a magazine reader to be told what it looks like from the other side of the printing press. The repetitive pages of advertisements and unlikely garments worn by a succession of starvation victims (some models make themselves feel full by eating tissues which swell up and fill the stomach) would not be paying or earning their huge fees but for the magazine’s ‘culture’. The thickness of the stationery, the flowers at reception, the handwritten thank you notes, the corporate Christmas cards are ‘all part of the brand’s DNA’ which justifies the premium rate charged for an ad page. And everybody involved in this business has their own self-conscious ‘brand DNA, often theatrical and designed to shock. One designer for example began his fashion show by sending hordes of rats down a clear Perspex runway.

By 2009, when Vogue Australia was due to celebrate its 50th birthday, it struck Kirstie Clements that she was the only person there with more than twenty years of corporate or cultural memory. Within two years, as her predecessors had been, Kirstie Clements – along with almost the entire editorial team – was unceremoniously dumped.

This short, readable memoir isn’t written out of spite or to take revenge. Kirstie still loves magazines and especially Vogue Australia; ‘I still believe in the magic,’ she says.