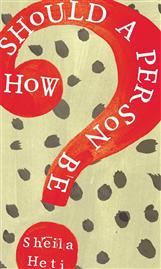

Published by Harvill Secker 24 January 2013

Published by Harvill Secker 24 January 2013

320pp, hardback, £16.99

Reviewed by Caroline Sanderson

Never mind how a person should be. How should a person read this book? I’m darned if this person is any the wiser 300 pages later.

This self-confessed roman a clef by Canadian writer Sheila Heti hasn’t baffled everyone. It arrived here from North America festooned with admiring quotes by the likes of Margaret Atwood and James Wood of The New Yorker, along with TV writer of the moment Lena Dunham, creator of HBO’s hit series Girls, to which this book has several times been compared. Its bizarre blend of philosophy, fiction, playscript, email and autobiography wowed a whole phalanx of US critics, with Dunham dubbing it: ‘A really amazing metafiction-meets-nonfiction novel’. For one critic, it was even ‘a new kind of book’. I can just about see what’s meta about it, but it didn’t strike me as a new kind of anything. Apart from a monster mash-up, maybe.

Sheila (for reader, it is she) and her arty-farty friends hang out in Toronto’s art galleries and cafés – and try and decide how to live their lives, having ‘weeded out’ all the ugly people. New BF Margaux is an artist and Sheila is trying to write a dreadful-sounding play, although to her credit she seems hell-bent on doing anything rather than write it. In between working shifts at a hairdressing salon (a job recommended by her Jungian analyst), she does way too much thinking and spends way too much time perfecting blow jobs for the benefit of her jerk of a boyfriend, Israel (about whose sexual proclivities we garner way too much information).

There are fleeting glimpses of the real trials of life, glinty flashes of truth. ‘Destiny became like an opaque, demanding, poorly communicative parent, and I was its child, ever trying to please it, to figure out what it wanted of me.’ Turning her back on that destiny leads Sheila to divorce her husband. Meeting him again later, they wonder aloud, ‘Why we pick certain dots and connect them, and not others?.’ I did love that image of life as a dot to dot puzzle. And occasionally I think I recognized a laughable irony or two, such as when Margaux decides autism is ‘an advantageous trait’, or when the Jungian analyst attempts to interpret Sheila’s dream about flying: ‘Did you imagine writing the play would get you somewhere higher and better, just like an airplane does?’

Deciding how, and what to create in a world overpopulated with creations is certainly a dilemma worthy of discussion. And – though I hesitate to use the word ‘blowing’- it is mind-blowing when you’re young to realize that ‘one is a reproduction of the human type: one sleeps like other humans, eats like other humans, loves like other humans, and is born and dies like other humans.’ But did I empathize with Sheila’s metaphysical plight? Nah, not a lot. And ultimately I found Heti’s portrayal of female friendship – something I always like to read about – disappointing. Perhaps I was just wondering way too much about why I’d been told that Margaux and Sheila wear dirty underwear.

But there’s worse than unwashed smalls on page 2, where Sheila declares that how a person should be is a celebrity. ‘By a simple life, I mean a life of undying fame that I don’t have to participate in.’ I never quite got over page 2. By page 4, we also know that giving head often makes Sheila gag. I never quite got over page 4 either.

Quite possibly I am not deep enough a person to read this book, let alone review it. I do dimly remember once having time for a more self-obsessed life when I wondered for a bit how I should live, and how creativity might play some part in that living. But you know how it is what with having to work, and pay the rent, and attend to other people’s non blow-job needs. How should a person be? Well, write a book about it if you must. But you might be better if you don’t.