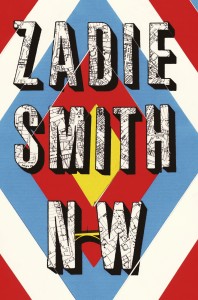

Published by Hamish Hamilton 27 August 2012

Published by Hamish Hamilton 27 August 2012

304pp, hardcover, £18.99

Reviewed by Charlotte Moore

‘NW’ is north-west London, specifically Willesden. Zadie Smith’s new novel follows four characters who grew up there on the same estate and went to the same school, a ‘thousand-kid madhouse’. Now in their mid-thirties, none have strayed very far geographically from the scenes of their childhood. But in terms of income, aspiration and social class, they have diverged immeasurably. Perhaps predictably, the most ‘successful’ is also the unhappiest.

Three of the characters are given their own section, with prose style to reflect their several preoccupations and ways of thinking. We start with Leah, pale skinned and red haired, with a judgmental Irish mother, a useless philosophy degree, and a lovely French Algerian hairdresser husband who longs for a baby. Leah’s narrative mainly happens inside her head: ‘At least with eyes closed there is something else to see. Viscous black specks. Darting waterboatmen, zigzagging. Zig. Zag. Red river? Molten lake in hell?’ The reader has to work quite hard to make sense of Leah’s world from her fragmented observations, but the effort is largely rewarded, thanks to Zadie Smith’s eye for the telling detail and exceptionally keen ear for word patterns and speech rhythms.

Leah is closer to the edge than anyone realizes. Her sense of identity seems entirely bound up in her possessive love for her husband, Michel. Leah’s whiteness puts her in a minority both in the book and in this neighbourhood. She seems to want to allow herself to be absorbed into Michel’s blackness. At work – she has an unfulfilling council job – her black co-workers show half-joking resentment of her marriage: ‘No offence, but when we see one of our lot with someone like you it’s a real issue.’ But when she takes Michel to dinner parties with her university-educated professional friends, his simplicity embarrasses her.

Michel is honest, Leah devious. She allows him to believe that she, too, wants a child, but she terminates her pregnancies in secret. (Why does she pay for an abortion? And why, later, does she steal contraceptive pills from her friend Natalie’s bathroom cupboard? These things have been freely available for decades, few questions asked. This is a rare example of Zadie Smith slipping up on details.) Leah is trapped in a self-spun cocoon. Release of a kind comes when she is conned by a junkie she remembers from schooldays; the encounter and its aftermath propel her, painfully, out into the world.

The second story belongs to Felix, erstwhile drug dealer, son of a parasitic Rastaman. Felix has found true love for the first time with the beautiful and wholesome Grace (neither name is accidental), but he has one last journey to make, to lay the ghosts of his old life. This journey, through London at sticky Carnival time, from the Willesden estate to a car deal in Mayfair to Soho and the Hogarthian squalor of his trustafarian ex-lover’s drug den, will be the last he will ever take. It has much in common with Mrs Dalloway and is the strongest, most fully realized section. Felix would have been a film director in another life, so his story unrolls like a film. It feels almost as if he is scripting his own fate.

The third section feels the least satisfactory. Keisha Blake, Leah’s best friend since Keisha caught her by the red plaits and saved her from drowning at four years old, has come the furthest. She is a highly paid barrister; she has married a public schoolboy and changed her name to Natalie. But the smart house and the business suits, the nanny and the two beautiful mixed-race children cannot give her a sense of purpose or coherence. Furtively, on line, she discovers that ‘on the website she was what everybody was looking for’, and embarks on a sordid double life in an attempt to shore up her disintegrating personality.

To express this disintegration and detachment, Keisha/Natalie’s narrative is divided into no fewer than 185 short scenes. Some of these succeed, as when Natalie returns to the council flat of her childhood to offer unsought financial help to her sister Cheryl, who lives there with their mother and her own three babies. As the sisters exchange sharp home truths over the body of a sleeping four-month-old, all the unresolved age-old tensions rise to the surface, painful and wholly believable; ‘ “But no one in here is looking for your help, Keisha! This is it! I ain’t looking for you, end of!”’ Too many scenes, however, are coy, whimsically oblique, or just dull. Scenes are told as emails, as quiz answers, as stage directions. Smith’s experimentalism can be witty – she teases the reader with verbal puzzles. But sometimes it’s just irritating, as when a whole lot of full stops pop up unbidden. ‘Yes. Said Natalie Blake. Still smoking. PUT IT OUT. Shouted the old lady.’ Why?

The fourth character, Nathan Bogle, has no narrative of his own – he is dispossessed in most senses. An irresistible ten-year-old, a talented musician, a promising young footballer… now, Nathan’s toes stick out of the holes in his trainers as he sells stolen Travelcards outside the tube. ‘So sad’ is how Leah’s mother sums him up. An object of revulsion, fascination, fear, and a kind of dark desire, Nathan has a life that intertwines with those of the other three and pulls their stories together. NW is about class, race, money, family, London, but above all it seeks to show how patterns laid down in childhood shape adult behaviour. Nathan Bogle is not so much a character as an externalization of the subconscious drives of the other three. His name is oddly similar to Natalie Blake’s; in the end, is he her rescuer or her nemesis?

NW has its irritations and its longeurs, but it is subtle, thought-provoking and endlessly inventive.