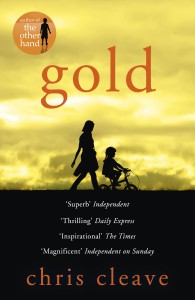

Published by Sceptre 3 January 2013

448pp, paperback, £7.99

Reviewed by Elsbeth Lindner

Legendary Scottish football player/manager Bill Shankley liked extremes. As he famously commented: ‘Some people think football is a matter of life and death. I assure you it’s much more serious than that.’

And Chris Cleave is fascinated by extremes as well, as is evident from his smartly-timed new novel Gold, which appeared in hardback a few weeks ahead of the Olympiad and is devoted not only to the business of competitive sports but also ‘the Olympics of parenting’, Cleave’s term for caring for sick children. Pitching a race for the prize against the health of an eight-year-old child and driving them to a neck-and-neck finale is the highpoint of the new book by this unusually gifted writer who has carved out his own literary niche through a combination of sharp plotting skills, empathetic (often female) characterization, a core of moral commitment and a homing pigeon’s instinct for the zeitgeist.

Despite its shrewd timing, Gold doesn’t quite have the prescience of Cleave’s first novel, Incendiary, which imagined a terrorist attack in a football stadium and was scheduled for release on 7/7/2005, nor the politics of his second, the bestselling The Other Hand, but it does an opportune and thrilling job of exposing the inner world of competitive cycling – the tactics, the training, the diet, the physical demands and the ecstasy of excellence.

Three athletes take turns as central character, although it’s the perfectly matched women, Zoe Castle and Kate Argall who dominate the story. BFFs as well as rivals, they also fall for the same bloke, Jack Argall, six foot of sculpted Scottish beefcake, a gold-medal-winner, funny, charming and a good dad to boot.

If Jack is an only-slightly flawed superhero, Kate and Zoe represent the Janus faces of the sporting coin: sunny and balanced versus driven and dark. Kate is caring, therefore has weaknesses as well as relationships: she lives in the real world. Zoe, blessed with model looks but haunted by a childhood death, describes herself as ‘ugly on the inside’. She sleeps around, takes risks and no prisoners, and is sociopathically ruthless in her pressure to win.

Cleave’s scenario could, then, be considered loaded even before the problems of the sick child are added to the mix. That ingredient pushes the story to the emotional edge where less skilled authors might tip over from pathos to bathos. But Cleave’s fine shading, his use of the often unspoken language of expectation, responsibility and meaning between Star Wars-obsessed, leukaemia-suffering Sophie and her parents is persuasively done.

At its best, Gold is as compelling as the winner’s urge to die trying. It’s smart, superior entertainment capable of offering, as in its very first scene, tension real enough to raise the heart rate. But its construction, a complex sequence of revelatory flashbacks, while clever, is also a little draining. The background, for much of the novel, is the foreground, with forward motion coming relatively little and late. And pitting Kate and Zoe’s race-for-a-single-place at London 2012 versus Sophie’s sudden collapse, alternating scenes as if on a split screen, is undoubtedly fast-paced but never entirely buries a sense of calculation.

As the adrenalin evaporates, readers may wonder if, like the Games generally (though not 2012 in fact), the climax quite lives up to its billing. But that’s sport for you: life and death to some, mere bread and circuses to others.